Collection

Delivery on the Rhine – by Claudia Schaefer 1996

Claudia Schaefer Innerharbour Duisburg

Delivery on the Rhine

National boundaries are often barriers that have come about by chance. To overcome them on an economic level is one of the goals of the European Community. Much more difficult to overcome and more fundamental are the cultural barriers. They are more deeply rooted and cannot be overcome by treaties. Europe's external shape has been realized by contracts, and now the internal cooperation has to follow.

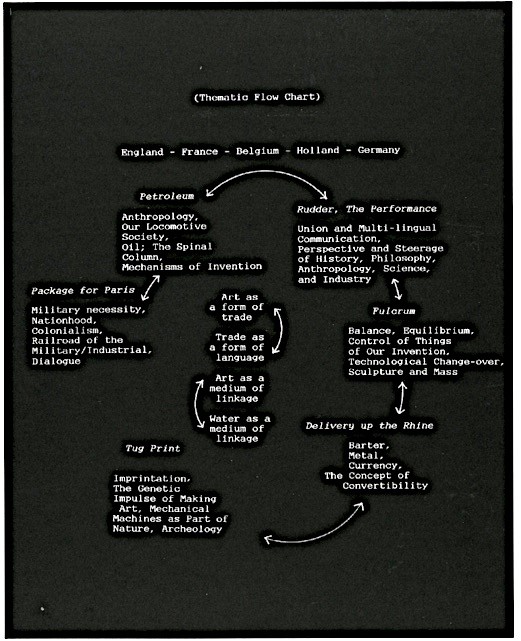

Through his art, Max Couper is engaged in making European connections on the most ancient of trade routes; the waterways.

His journey on the Rhine makes connections between trade and economy; culture, art and communication; and to the parallels that exist between the transport of goods and the transport of ideas. Water is defined as the physical element and basis for realizing the artworks, whilst also serving as a metaphor for the flow between borders; the connection between past and present, and how nations communicate.

`As the tail steers the fish, culture is determined by history' (Max Couper). The historical context, which played a major role in choosing the route's destinations, runs like a red thread through the series of events. At the first stop in Antwerp four archetypes personify the anthropologist, the scientist, the philosopher and the industrialist, as representatives of our society. Four different angles that reflect on the past and present under different criteria.

This poses the question of how history and past epochs are interpreted? Every era re-interprets history under its own criteria, basing its theories and speculations on its own view of the world. Contemporary history writing in the united Europe is going to look different from the interpretations of the recent past, including in cultural affairs. The writing of post-industrial history will redefine the relationship of man and machine, nature and industry. Already some former bulwarks of our industrial production have become fossils, and from one archeological point of view, became part of nature (Tug Print, Hanover).

The question of how the post-industrial era rewrites history becomes apparent in Couper's work for Duisburg; The Steel Fulcrum, the room that moves when you walk in it. In which, according to the principle of cause and effect, movement is no longer caused by the physical element of water, but by the participants' activity inside the aesthetic object; a machine of transportation adapted by the artist. As in the industrial age, when machines that were developed by man determined his life and made him dependent upon them, so in the post-industrial era a liberation must follow. This idea has been transformed by the artist into the work of art, the machine, which is kept in motion by the spectator.

The age of the information superhighway, the inter-net and cyberspace, in which man stays anonymous even during economic transactions, is juxtaposed by Couper with methods of past epochs, when trade consisted mainly of physical travels and personal communication. In those days, cultural exchange grew out of personal contact between traders, and new ideas originated out of contact with someone else's customs and traditions, their different everyday objects, clothes and language. And the exchange of goods was often synonymous with the exchange of culture. For example, traders would bring with them opulent works of art as presents for fostering the business climate. Is not art and culture today still active in opening trade? This traditional bringing and taking of goods, together with the personal contact is part of Couper's whole series of events from Antwerp to Hanover. Thema-tically, this aspect of trade culminates in Delivery on the Rhine in Kaiserswerth, an ancient trading post on the Rhine. In Kaiserswerth Couper relives an old trading tradition. He docks in front of the former customs building and delivers an edition of steel and paper currency pieces, which are intended for the Ute Parduhn Gallery. Steel, previously the main trading product of the Ruhr's heavy metal industry, once again becomes a trading object for the artist and gallery. A commercial transaction becomes a self-reflecting art event, in which packaging, transport, presentation and sale; are form and content alike. Couper demonstrates that on an abstract level, economic transaction can easily be compared with the organization and realization of art. But whereas politics and economics trade in material goods, art —according to a broader definition of the term — increasingly assumes the role of dealing in immaterial goods, ideas and concepts. The principle and mechanism behind both systems are identical in many ways, from the concept of a project to the finding of partners; from financing to realization. The main difference is in the critical reflection; the difference between economic and intellectual capital.

Max Couper's artwork is determined by two coordinates; a sensitivity for historical processes, and by a rational and abstract understanding for the economic mechanisms in our society. Economics and art are essential constituents of our culture, forming a unity in Couper's artwork. The artistic intuition into thematic systems — communication and dialogue (Rudder, the performance, Antwerp); economics and power (The International Petroleum Conference '96, Rotterdam); man and machine (The Steel Fulcrum, inner harbour Duisburg); industry and nature (Tug Print, Sprengel Museum, Hanover) — shows the individual interpretation and the signature of the artist. Whilst the rational execution, based on economic principles, suggests a reductive abstraction and critical distance. Without this rational structure the artistic intuition remains amorphous and incommunicable. In Couper's artwork the two basic coordinates of artistic creation — intuition of the senses and rational abstraction (reduction) — form a stringently convincing unity.

Dr Claudia Schaefer Director of the Cubus Kunsthalle, Duisburg

Researcher for Duisburg Innerharbour.