Collection

European Business Conference Duisburg – dialectical artwork transcript 1997

The European Business Conference Duisburg ‘97

Presented at the opening of The Plot exhibition Part of The Steel Fulcrum project Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum Duisburg European Centre for Modern Sculpture

The London delegation, on route. Left to right – Max Couper, Nick Skeens, Peter Wilder

Keynote speakers

Nick Skeens (Chair) ex British television news editor

Professor Ulrich Director Sprengel Museum Hanover

Krempel Ute Parduhn Gallery Düsseldorf

Ute Parduhn Artist, USA

Terry Fox Director Cubus Kunsthalle Duisburg

Dr Claudia Schæfer Cultural manager on behalf of Mercedes

Karl Hussman Benz

Herman Pitz Artist, Düsseldorf

Dr Stephan von Exhibitions director Art Museum

Wiese Düsseldorf

Excerpt is from a transcript of the first part of the conference

Nick Skeens (Conference Chairman)

Let me raise the first issue and ask this question: What can art gain from doing business with business, and what can business gain from doing business with art? Max, how does this relate to the diagram we all have in front of us?

Max Couper

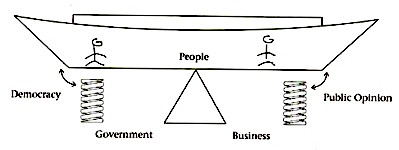

This diagram represents the conflicting influences on my project The Steel Fulcrum since I arrived in Duisburg, which have ended up being incorporated into the artwork. On the one side I am working with people from a public museum, The Lehmbruck Museum, who in turn are working to realize my projects with local partners and a corporation in the harbour.The Steel Fulcrum, my main project for Duisburg started out as a metaphor for ‘people and machine’ but, since the problems I have encountered here in Duisburg in making it, it has become something more. More about how people, or society – a thing that we are all inside together – is balanced between the

conflicting influences of business on the one side and government on the other.

In the artwork, as in society, there is a very fine balance of conflicting weights at work, which are cushioned in their effects by various checks and safeguards. The steel springs in the artwork could represent two of the main buffers protecting society. Between business and people is the buffer of public opinion – a necessary protection because otherwise business will tend towards the interests of itself and its shareholders first and foremost. The buffer between government and people is the concept of democracy and accountability. This is the much simpler relationship of the two in many ways because it is more generally understood, and it is a much older relationship than that of people and corporate big-business

Nick Skeens

How have you tried to come to terms with this during your series of European events?

Max Couper

I have tried to give situations the chance to speak for themselves – so I don’t prejudge events too much. Art is partly what happens to you. In the same way that an artist paints a picture of what he or she sees, the landscape that has confronted me here in Duisburg has been a collision of politics, business, and culture – hence what the art has become about. Since I left London and crossed the Channel last year there have been a set of different circumstances in each place. In Antwerp, for example, there was a very smooth collaboration between the city and its partners. My conclusion is one that can only come out later.

Nick Skeens

Let us turn to Professor Ulrich Krempel. Do you believe that as Western society develops, and many responsibilities move away from the State towards business, this is a good or a bad thing for art in general?

Professor Ulrich Krempel

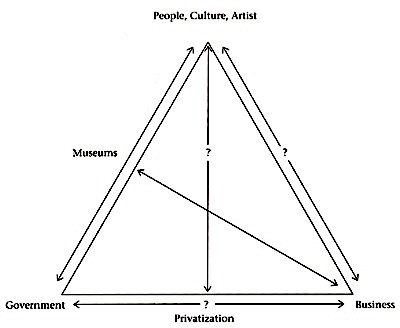

I think the situation is probably very different everywhere in the world. If you look at the situation here in Germany you’ll notice you still have a lot of influence and funding of culture and art by the State – which means public money – which is good for art in general. At least in democratic times this means a committed influence on the development of art. On the other side there is a natural relationship between art and business.

About 490 years ago Dürer and his wife, who was a merchant, travelled to all the fairs in Europe to sell his work. At that time there were a lot of borders in what is now Europe, around which his wife worked through her commercial contacts, and they sold work. So there can be a helpful relationship between artists and people who care about the presentation and distribution of art, i.e. the dealer.

Nowadays there is a necessary relationship between all parts of society. Not far from here, in Düsseldorf, the artist Joseph Beuys, a lot of whose work is on the floor below Max Couper’s exhibition, held the view that every person working and living in different fields can be an artist in his or her specialist field –and I think there is quite a lot of truth in that. There is the possibility of intense creativity in all fields of human work. The relationship between fields can operate in a dignified or a not so dignified way. When business, as happens every day, tries to steal ideas from art, it is bad. But when there are stable and intense relations between the two it is good.

There are others who will dig deeper into this but what is obvious is that we have a complicated situation. Side A needs side B and side B needs side A, and sides A, B, and C all need each other. Without the development of ideas and a look further into the future – which is usually initiated by the artists

– neither society nor business will be able to develop and we will not have real aims. And it is aims that create an intense relationship between all partners.

Nick Skeens

Taking up your term ‘aims’, perhaps one problem is establishing what are the aims of business in its relationship with art. I want to turn now to a representative for Mercedes Benz. Why is it that people like Mercedes Benz become involved in art projects?

Karl Hussman

As you know, Mercedes Benz do a lot of art and culture sponsoring. The aim in this is mainly to help represent the products. We see the products as the result of creativity, whose lifestyle associations can be enhanced by being linked to particular kinds of art. Also, people who enjoy culture and like art are one of the target customer groups. Sponsoring art is a means of self-representation, and in this context you could say that art serves business.

Nick Skeens

Can I have a reaction from an artist, Herman Pitz?

Herman Pitz

I am afraid, gentlemen, I can’t handle this sort of approach from business.

(He walks out of the conference)

Karl Hussman

Max, as an artist you’re dealing with means of transportation. I think we have something in common there.

Professor Ulrich Krempel

I am a little bit amused by this relationship that is developing between the two of you – with Max Couper who has never been in danger of being corrupted by anything. I don’t think the clever art sponsorship works quite like this. I remember two kinds of art sponsorship that really looked very bad. First, when McDonalds wanted to sponsor a gallery in Hamburg and they paid for the catalogue and on the front cover you had a big McDonalds sign. That was one kind, and the second was when a big company sponsored the Munch exhibition in Essen and it was not the museum director who was the one to greet the press at the press conference but the boss of the enterprise. That is in bad taste. That doesn’t work any longer.

Nick Skeens

How do you see this, Ute, as a gallerist working with Max?

Ute Parduhn

You have the gallerist in between the business and the artist, and it is our responsibility to help manage some of the problems you’re seeing here today.

Max Couper

Terry, could I ask you to comment as an artist from an American perspective?

Terry Fox

I don’t have any business experience. But I was involved in shows that were sponsored by business – which I didn’t find out until later. In the United States it is very different. You get government funding. I think I got fifteen thousand dollars from the government five times. In the United States you get the fifteen thousand dollars but you don’t have to have a specific project. You just get the money and at the end they ask you what you did with it. So you could say, well, I rented a studio and I worked but I haven’t been able to have a show yet (and

so on). In the United States it is very difficult to get business sponsorship.

Nick Skeens

Max, how did things work with your project for Duisburg?

Max Couper

The museum exhibition has worked well and the Fulcrum project for the harbour was fine. Then all kinds of bureaucracy started, creating tensions that, although I didn’t realize it at first, actually enriched the tensions within the artwork, giving it an unexpected edge. Problems sometimes have a way of revealing the actual mechanisms at work below the surface. I could never have set out intentionally to create an artwork that in itself reflects all the difficulties of its own creation, which has happened with the Fulcrum. But in the end I may give up on making the Fulcrum here and make it in Düsseldorf.

Dr Claudia Schæfer

I’m sorry to hear this. With the end of public money for art it can be very difficult for artists here in Germany because business does not really understand art. Business sponsoring here is all about giving to the most famous names because there is much more publicity.

Nick Skeens

Has it not always been the case that if you were a famous name you would naturally get more support? Perhaps Dr Stephan von Wiese, curator and art historian, would comment on this?

Dr Stephan von Wiese

I would like to co-operate with more companies but they do not want to work with me because I make a programme that is not of interest to them. They want to have the big names and be sure that they promote their products. So they make exhibitions with old, famous artists who are already dead.

(Conference continues)

The European Business Conference Duisburg ‘97 was staged as an unannounced event, complete with conference table, in the middle of the official opening of the The Plot exhibition.

Couper’s intention was to replicate some of the tensions that were taking place in the development for Duisburg of The Steel

Fulcrum, the models of which were on show at the opening. The result was one of some confusion for the people attending the opening, who could not comprehend why a conference was taking place there and then, which only increased the overall irony of the event.

Despite full support from the local people, press, the city museum, and the main harbour, The Steel Fulcrum was eventually never made in Duisburg as intended because of difficulties at the inner-harbour corporation site. The artwork was instead transferred and realized at short notice in Düsseldorf, co-ordinated by Ute Parduhn.

Financing for the making of The Steel Fulcrum in Düsseldorf came from the Lehmbruck Museum, who purchased a collection of Max Couper’s work for their permanent collection.